Scrum on steroids: a Holacracy development process

Written by Mark Vletter on 1st December 2015

Over the last year, our team tripled in size. We adopted Holacracy and learned a lot of new methods which made the overall development process better. I feel we now have a real solid workflow. Some of the stuff will be familiar to you, some stuff will be new and might improve your development process as well.

Two projects

We are currently working on two big projects. VoIPGRID, our wholesale cloud telephony (PBX) platform and HelloLily, our next generation relationship manager (CRM on steroids). For this story, it is important to know how these two projects differ.

The VoIPGRID platform is a live system which is used by businesses all over the world including organizations like hospitals and fire departments. There is very little room for error here. All systems are fully redundant over multiple locations.

HelloLily is currently used by four companies and has a pre-Alpha stage. Where the four companies do rely on Lily for every aspect of their communication – from email to deal and case registration – a fault will, generally speaking, have little impact, besides frustrated users.

I’m going to dive deeper into the process of HelloLily because I’m actively involved there. Lily is built like you would an MVP with a very short Build, Measure, Learn cycle. There are three common starting points in the development process. These starting points are the Holacratic roles Milestoner, Supporter and UX prototyper.

Problem or improvement

The three starting points

The Milestoners

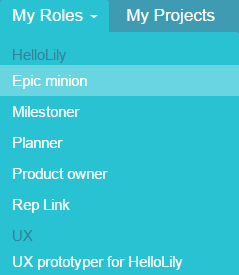

The Milestoners create the roadmap for the product. There are four Milestoners at HelloLily. Each person filling the role has a focus: Business, Users, Technology and UX. In doing so, all aspects of the product are represented.

We have a Product Owner who has a final say on big issues, but creating the roadmap is a team effort. It has made our product better. The fact that product vision and future is more distributed makes the Product Owner role less heavy. It gives better and balanced output and gives everybody more ownership over what we are building and how we want to build it.

The fact that product vision and future is distributed gives better output and gives everybody more ownership over what we are building and how we want to build it.

The Supporter

Next to the Milestoners there is the Supporter. He creates tickets based on bug reports and feedback we get from users on HelloLily.

The UX prototyper

Then there is the UX prototyper. He actively engages with users to seek the deeper lying needs behind what the users are telling him they want from the product.

User experience

Now it’s time for the UX people to get more involved. Tickets created by the Supporter usually don’t end up generating UX work. Work that comes from the Milestoners does create UX work. We try to complete the Build, Measure, Learn cycle a few times by prototyping and wireframing before we actually start coding. The output of UX used to be a wireframe, but today the UX circle often creates the front-end HTML or prototype as well.

Naming the milestones

One more thing. Before you start coding, you want good names for the Milestones. Let me give you an example. It’s boring to work on ‘Pre Django update prep’. Working on ‘Django Unchained’ however…

Tickets

Priority

The Milestoners created the roadmap of HelloLily, which include various Milestones of the product. The Milestoners, Supporter and the UX prototyper have created various tickets. Based on the roadmap it’s now time for the Planner to prioritize stuff. There are various kinds of tickets:

- Epics (a groups of features which combined create a new functionality)

- New features

- Improvements

- Bugs

- Tasks

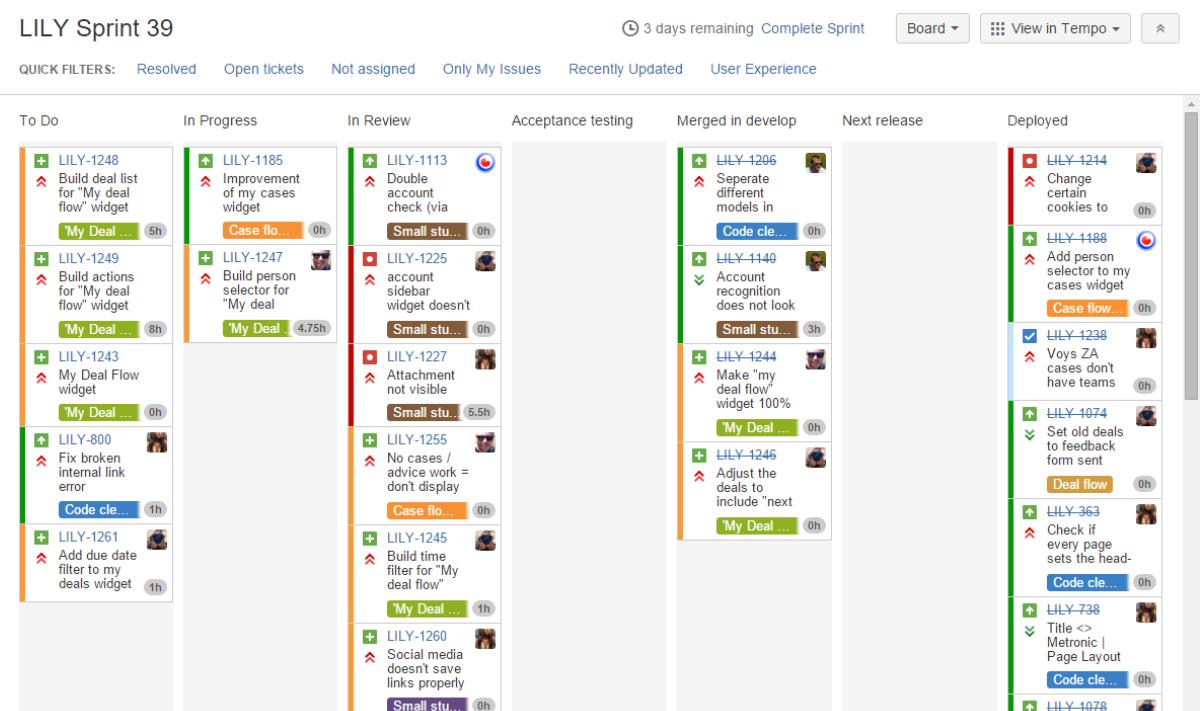

We try to keep the tickets under 4 hours in size, because the smaller the tickets are, the easier they are to scope. Tickets are then related to a Milestone and put into JIRA, a proprietary issue tracking product, as you can see below.

Small stuff

There is one special kind of ‘Epic’ we use. Each Milestone has a “Small stuff for version xyz” epic. We want to use the small stuff version to get a historic feel for the maintenance tickets we have for each version. We have become really good at scoping, but it tends to get difficult to give a long-term estimate for release dates of Milestones. A big part of this are these maintenance tickets.

Sprints

A sprint

Our sprints last two weeks. We tried one week for a while, but that didn’t work well focus wise because some people switch projects often.

Focus

Each sprint has a focus. That’s usually an Epic we want to finish in the sprint. We try to finish one Epic before we move to the next Epic. We also try to work on one Milestone at a time, but that’s not always possible.

During the Holacratic Tactical meeting, the teams get updates on current Epics and an intro to the upcoming Epics. This enhances the focus of the sprint and gets everybody up to par. The updates and intros are given by the Epic Minion. This is the person who knows the most about the Epic. It’s often the same person as the Milestoner, Supporter or UX prototyper who was responsible for the existence of the Epic.

Sprint planning

Work hours

The Planner plans the sprint. We start by looking at the number of available hours. We only take into account the number of work hours a developer is going to have in a week. An example: we don’t detract hours of these work hours for stuff like the sprint planning. Stuff like that is settled in the velocity.

Velocity

Velocity is the number of hours a developer booked on his tickets over the last sprint divided by the amount of work hours he had in that same sprint. This gives a percentage.

Velocity during the previous sprint * the work hours for the upcoming sprint = the amount of available hours.

Scoping the tickets and ticket poker

Now the fun begins. Every ticket is scoped using ticket poker. Everybody with skin in the game during the sprint – including the Product owner and Planner – gives his blind hour estimate for each ticket. Then everybody shows their estimate and extra explanation is given. There is some small debate after which we settle on the scoped hours. The explanations and possible ticket solutions are written down as comments for the tickets. Sometimes tickets are assigned to one of the developers because that particular developer is the right guy for the job.

Because we write open source code we want to write maintainable code. That means the code is up to par with our style guide, that the code is testable and that the code is of high quality.

Because of these parameters the hour estimate we give includes:

- Coding of the ticket

- Writing tests

- The code review process

- Possible code refactoring

There have been some – external 😉 – questions why the Product Owner is part of the ticket poker process. There are various reasons for this:

- We have technical Product Owners and Planners so their insights are valuable.

- We want to code for a 10 but deploy when it’s an 8. The non-developer roles have to keep this in balance.

- It’s good that non-developers get a feel with how much or how little work goes into certain types of decisions.

Sounds like a lot of time

The process might sound like a lot of time, but the fact is that the tactical meeting usually takes only 40 to 45 minutes a week and the bi-weekly sprint planning is usually done in under an hour.

Sounds like a lot of people

It might also sound like a lot of people are involved, but that’s not the case. Yes there are a lot of roles, but everybody can have multiple roles.

The actual coding

During the coding itself the developer might have questions about the ticket. If it’s a ‘how should this work’ question it is answered by the Epic Minion.

Developers creating tickets

There are some rare cases where a developer creates a new ticket. Reason one is that he finds stuff that needs to be fixed but is off scope. Reason two is that a ticket is actually bigger than expected. In both cases, the developer scopes the ticket. It’s up to the Planner whether or not the new ticket is placed into the existing or another sprint. If he places the ticket in the current sprint, he has to take stuff of equal hour amount out of the sprint.

Code for a 10, deploy on an 8

During the coding, we have two basic rules. One: “It’s done when it’s done”. It’s the developer that decides when the ticket is done and nobody else. Two: “We deploy when it’s better, not when it’s perfect”. If the finished ticket is an improvement compared to the old system, we go live.

We deploy when it’s better, not when it’s perfect.

Because the product vision is a shared vision, it’s not a developers VS Product Owner or Planner kind of project. The two rules have also enabled us to deploy high-quality stuff and – because we deploy every week – keep a very short Build, Measure, Learn cycle.

Final thoughts

Where we can improve

We can still improve on our long-term planning and we hope that the Small Stuff Epics are going to help. I would love to have accurate three month estimates for Milestones. It makes it easier for developers and users to manage expectations and creates happy moments.

I would also like to enhance the Measure stage, especially when we deploy Epics. How is the new stuff being used, where do users click and how much is a certain part of an Epic used. I feel we currently have too little insights in this.

The biggest learnings

What has improved over the last year is that we are building the right stuff far more often. The fact that we run through the Build, Measure, Learn cycle before we start coding is very powerful.

We receive rapid and in-depth feedback on the product by deploying every week. Weekly deploys and deploying when it’s better not when it’s perfect has also enabled us to build more of the right stuff and adjust in time when it’s not exactly what the user wanted.

The shared vision, the alignment, the focus and the distribution of responsibilities has enabled us to truly work as one team. That might be the biggest learning of last year.

Your thoughts

No comments so far